Context ? (you mean external)

Learner context is believed to be the participants' knowledge and skills, their cognitive environment, filtered as it were; it is often meant to include learning tools. I argue that tools (technical means) and attitudes and dispositions (motivation, varying emotions, affect) are to be separated, at this early stage, from the cognitive just as institutional agency and prescriptions need to be distinguished from academic necessities and requirements. Learner context needs to be considered, first, in the cognitive aspects since our object, our responsibility, is education and we objectively need "approaches to teaching and learning that don't make assumptions about the motivations and interests of students" (Pegg). To distant learners, institutional context is external, foreign, and few will ever give a second thought to the pedagogy behind a schema.

For the purpose of educational design, I do separate learners cognition from their motivation, affect, and context because, in a design perspective (and not field work in the classroom or online environment when design is done and running), the contexts (i.e., design context: our institution, establishment) (i.e., teaching context: classroom or online learning environment) (i.e., learning context: private, personal, at home or office) are not yet joined but will be eventually, although very loosely and disconnectedly in the "post-temponormative" affordance of online environments (Ihanainen and Moravec 2011:36). If the design environment itself is institutional or corporate, then, in that design perspective, learner context is remote. Conversely, where learners are actively engaged with processing and learning or debating new knowledge, the institutional context is at least external to them and the focus is on content.

This student also sees the course as an entity, but in terms of something with which/whom he needs to negotiate. The people designing the course, the people delivering the course, the people administering the course, are all seen as one entity with no differentiation as to roles and responsibilities. The course is seen as a significant other with whom to negotiate, it could even be seen as an opponent. (Williams 2008:56)

Further, no 'internal' context needs to be construed. There is, objectively, no 'internal' (uncommunicable or uncommunicated) context unless bordering on philosophy of mind (not going there except for the private, intimate metacognitive). In this respect I like to remind myself of Wenger's approach whereby "models of communicable knowledge" need only be considered, that is, "a representation of knowledge very broadly, as a mapping of knowledge into a physical medium" (Wenger 1987:312).

As well, when preparing, designing a course or module, the concern is with curriculum, knowledge. Indeed we make room for communication and collaboration, but we don't know yet what will be conveyed; again there is no reason to presume of any entity's 'internal' (uncommunicated and often uncommunicable) context. In my design tasks, I can further leave out the learner's private sphere because there are basic institutional requirements or prescriptions addressing that: own or access a computer with online connection, operate word processor and other software programs, navigate online, etc. In addition, from the moment learners are admitted and enrolled, I must presume that they are 'cognitively' able (although there are surprises or cultural challenges in the feedback). Likewise, I must presume that the learner has engaged into the admission and enrollment process, and paid tuition, and is therefore in an appropriate state of mind and mature enough (speaking of higher education). Then, where 'pedagogical' or 'post-pedagogical' characteristics are imparted to the design, it is usually a matter of institutional orientation or, as I have seen, the individual professor's overriding decision with respect to her discipline (for example, normative environmental or health and safety knowledge).

Metacognition

What little we know about metacognition provides insights on the learning process (how learning is effected and not 'what is learning'). This, in turn, is useful to outline a distant learner profile and characteristics. Metacognition is a very active if not comprehensive notion that includes self-awareness whereby "[e]xamples of self-awareness corollaries are sense of agency, Theory-of-Mind (ToM; making inferences about others’ mental states), self-description, self-evaluation, self-esteem, self-regulation, self-efficacy, death awareness, self-conscious emotions, self-recognition, and self-talk" (Morin 2011). Therefore, prying into learners' motives (motivation) should be excluded from the designer's concerns (especially where educational design is organised around work-based learning or a student workplan).

Metacognition is also defined as the self-management aspect of learning—or autonomy—and may be broken down to metacognitive skills: self-guidance, planning, conscious attention in action, regulation, piloting, anticipation, correction, assessing and diagnosing the situation at hand and adjusting one's approach as needed. The latter adjustment process drives the learner to gather new information or data and initiate or "engage into another planning-supervision-objectivation cycle" (Paquette, de la Teja, Lundgren-Cayrol, Léonard & Ruelland 2002:10).

... and programming (or control)

Older, seemingly unrelated concepts are germane to metacognition with respect to this self-applied cyclical approach. Let us revisit a flamboyant cybernetic definition of learning proposed in the early 1950s:

I repeat, feedback is a method of controlling a system by reinserting into it the results of its past performance. If these results are merely used as numerical data for the criticism of the system and its regulation, we have the simple feedback of the control engineers. If, however, the information which proceeds backward from the performance is able to change the general method and pattern of performance, we have a process which may well be called learning. (Wiener 1950,1954:61) [italics added]

Learning is deliberate...

... and, for active learners, it not a by-product or result of exposure to context or environments. But self-awareness and metacognition (self controlled cognitive cycling) are not the only items of focus in the learning process; they largely depend on volition and on deliberate action; let's call this 'attention' and read again a crucial AI (artificial intelligence) lesson from a not so distant past (yet pre-MS-DOS):

In particular, the learning participant must have a need to cooperate in order to learn the topics in a conversational domain, which he has agreed to do in the initial contract. The other participant must be in a position to provide this cooperation and foster understanding. Finally, insofar as procedure sharing or program sharing depends upon local synchronisation of the brains or processors involved, the occasions of a strict conversation are intervals of partial synchronisation between the participants during which they both attend to the same topic. Notably, such occasions are rare in nature. Brains, unlike computing machines, are not a priori synchronised by a master clock and it takes an act of attention to secure synchronicity. (Pask 1976:6-7) [italics added]

Psychological distance

With respect to learner context, another approach is useful to tie-in 'distance' with 'learning': psychological distance and social distance. According to Nira Liberman (2007), social distance is defined as hypotheticality, i.e., a zero point which is my direct experience of the here and now and is different from anything else—other times, other places, experiences of other people and hypothetical alternatives to reality (Liberman, Trope & Stephan 2007:353). Yet, social distance and hypotheticality, and spatial distance, and temporal distance "all share a common meaning as instances of psychological distance" and are interchangeable as they all involve a higher level of construal. "A high level construal represents actions in terms of one’s primary goals, whereas a low level construal depicts the secondary/incidental features of these goals (Higgins & Trope, 1990)." (Basoglu and Yoo 2012:221-222)

Learner distanciation

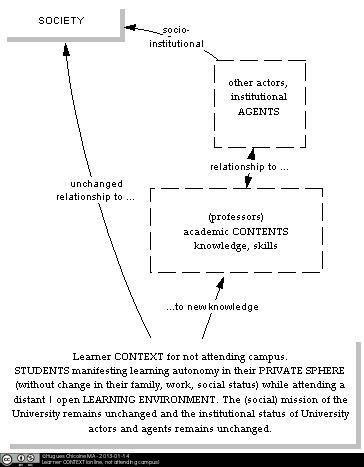

Liberman's theory of social distance bring to a halt the social contradiction of roles often associated with distant education and offers a key "that enables adult students to maintain their sense of status and power" (Garland 1994). Indeed there is definitely a form of social distance between the establishment and the learner when the latter is not required to appear on campus. Thefore 'context' , in its current educational metaphor (filtered), may not apply to distant learners. Distant learning introduces different dynamics that shift more weight on learners' relationship to knowledge (and less to professors who teach, less to socialising with peers and less to the socio-institutional sphere). This very specific type of learner distanciation can be mapped as follows to illustrate a more accurate learner context for distance, open education.

Open, distance educational design

This reflection is not intended to wipe out context but (i) to limit 'context' to the socio-institutional environment in which designers work and (ii) to replace the all encompassing technologically-centered design with a more appropriate representation of EDUCATIONAL (cognitive, academic) DESIGN. i.e., curriculum design, as follows:

Discussion

In the early years of instructional design (from the mid-70s to the late 90s) online courses were few and the ADDIE approach dates back to that period. Academic curriculum was adapted to whatever technology available (MS-DOS 1981, Windows 3.0 1990, Windows NT 1991, Win 95, Win 98). Today, computer systems and authoring software have introduced full layers of media, service professionals and agents in and around universities and colleges yet the very same curricula need to be learned (accounting, literature, etc.) — plus a host of new computer and software related disciplines. In universities, these layers of scholars and professionals are now integral to the institutional context and responsible for their academic disciplines. I am convinced that they too use an approach that enables their students to gather around a student workplan designed to promote learner development.

I have compared traditional teaching-learning with learning environements (none typical, really) and this is an attempt at exploring redefinitions of distance, open learning, from a learner's viewpoint. The viewpont is that of studying and learning, i.e., cognitive (not the computational metaphor of cognitivism, and, for most, learning not theoretically rooted in Technology except for word processing conceived as the most complex and far reaching system of writing ever afforded and used for both text and command line). In a nutshell, learners who do not attend campus activities do not come under the care or responsibility of the establishment. Their status shares nothing with the standard student status, i.e., that of a 'person with a future' — a futurible — as compared with the institutional status of professors and professionals governed by their respective employment conditions and workplans. Distance learners work from the private sphere and their attending of open, distance universities changes little to their relationship to and status within society until they are eventually granted diplomas. Meanwhile, hardly anything is changed in their personal contexts and it is somewhat deceitful to burden educational design with unverifiable, uncontrolled assumptions unless we simply wish (i) to gloss over institutional prescriptions, educational practices or actual approaches (they would, on the contrary, benefit from the exposure) or (ii) to awkwardly protect distance education against threats to its credibility or livelihood (Daniel 2010).

The ultimate question is not 'what is learning?'. Most of us are professional learners and yet we are at a loss for a definition. Let us ask instead 'how to support metacognitive efforts in online learning'. I think we need to provide and underline a few honest and engaging paragraphs on that very subject—, metacognition or the workings of cognition—in the study guides and in the course presentation pages and who knows, learners might just recognise themselves. We may even follow up with a few references or quotes on the sentiment of self-efficacy. The latter is somewhat motivational, and neither are 'interventions' in the tradition of pedagogy.

BASOGLU, K.A. and JUNG-EUN YOO, J. 2012. For business or pleasure?: Effect of time horizon on travel decisions. In Nicole L. Davis and Randal Baker, eds, Sustainable Education in Travel and Tourism. Annual Conference Proceedings of Research and Academic Papers Annual Conference Proceedings of Research and Academic Papers, Volume XXIV. 31st Annual ISTTE Conference, October 16-18, Freiburg, Germany. St Clair Shores, MI: International Society of Travel & Tourism Educators. (http://www.istte.org/2012Conf.pdf)

DANIEL, J. 2010. Distance Education under Threat: an Opportunity? Commonwaelth of Learning (COL). (http://goo.gl/2rHyD)

GARLAND, M.R. 1994. The Adult Need for « Personal Control » Provides a Cogent Guiding Concept for Distance Education. Journal of Distance Education, IX(1), 45-60. (http://goo.gl/xCTkX)

IHANAINEN, P. and MORAVEC, J. 2011. Pointillist, cyclical, and overlapping: Multidimensional facets of time in online education. IRRODL Vol 12, No 7, p.27-39.

LIBERMAN, N., TROPE, Y. & STEPHAN, E. 2007. Psychological Distance. In Kruglanski, A. W., Higgins, E. T. dir., Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (2Ed.). New York: Guilford Press, 353-381. (http://goo.gl/TJjRJ)

MORIN, A. 2011. Self-awareness Part 1: Definition, measures, effects, functions, and antecedents. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, Volume 5, Issue 10, p. 807–823, October. (http://goo.gl/y3dgQ)

PAQUETTE, G, de la TEJA, I, LUNDGREN-CAYROL, K., LÉONARD, M. & RUELLAND, D. 2002. La modélisation cognitive, un outil de conception des processus et des méthodes d’un campus virtuel. Revue de l’éducation à distance, 17(3), 4-28. (http://goo.gl/33CfY)

PASK, G. (1976) Conversation theory : Applications in education and epistemology. Amsterdam : Elsevier.

THORING, K., LUIPPOLD, C., MUELLER, R.M. 2012. Creative space in design education: A typology of spatial functions. International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education, 6 & 7 september 2012, Artesis University College, Antwerp, Belgium.

WENGER, E. 1987. Artificial intelligence and tutoring systems: computational and cognitive approaches to the communication of knowledge. Los Altos: Morgan Kaufmann.

WIENER, N. 1950,1954. The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society. Da capo Press 1988 (google books http://goo.gl/Qz0Kq p.61)

WILLIAMS, R. 2008. Affordances for Learning and Research. Project Report: Affordances for Learning. University of Portsmouth. (http://goo.gl/oryxZ)

Aucun commentaire:

Publier un commentaire